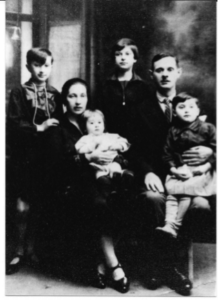

Hirsz Litmanowicz Gonjuch was born in Będzin on July 27, 1931 to Rivka and Szlomo Litmanowicz. Hirsz was the youngest of five children. With his siblings Golda, Masha, Sarah, and Nissim David they lived in a two-room, second-floor apartment at 70 Modrzejowska Street. Szlomo made boots while Rivka took care of the household and children.

They were a typical Jewish family keeping the traditions such as honoring the Sabbath and attending synagogue. Hirsz remembers Shabbat dinners of gefilte fish and challah bread. Szlomo died in 1933, forcing Rivka to find work outside the home to provide for the family. Hirsz’s eldest sisters Golda and Masha took care of him even after they married and started their own families. Golda married Monyek Meryn and they had a daughter Perla; Masha married Abraham Sylbergold and they had a son named Szlomo Leib.

Hirsz attended cheder where he learned Talmud and Torah and how to read and write in Hebrew. He was able to attend only the first grade in a Polish school in 1938. After Nazi occupation in 1939, Masha and Sarah worked in a shirt factory for the Germans and struggled to get enough food for their younger siblings.

During the stadium roundup in 1942, Hirsz avoided deportation because Masha and her husband Abraham worked in a factory the Germans deemed vital for the war effort. For the next year, Hirsz lived with seven other family members in one-half of a stable. In June 1943, the SS came to deport the remaining Jews to Auschwitz. Masha hid her brothers (Hirsz and Nissim David) under the bed. The next day, hungry and alone, the two brothers crawled out from under the bed to look for food. An SS officer put them on the last transport to Auschwitz.

Hirsz arrived in Auschwitz on June 24, 1943. Along with eleven other boys from Będzin, he was selected by Dr. Mengele to be part of an experiment on Hepatitis B. He was forced to act as Dr. Mengele’s messenger in Block 10. Hirsz witnessed firsthand the horrific experiments and tortures inflicted on the Jewish people. While in Auschwitz, Hirsz wrote a letter to his sister Sarah who was in the Sudeten mountains. He never received a reply, but he assumed she got the letter and was alive. This thought gave him hope during his internment. Sarah did survive the Holocaust and reunited with Hirsz after the war.

The eleven boys forced to be part of medical experimentation were sent from Auschwitz to Sachsenhausen in Germany. They were kept in one room and slept two to a bunk. Hirsz made fast friends with fellow prisoner Saul Horenfeld, with whom he stayed together after the war. Shortly after the boys arrived in Sachenhausen, the Norwegian prisoner Per Roth became a medical assistant. In 1945, when the Nazis retreated, the Germans wanted to kill the boys before abandoning the camp, but Roth convinced them to spare the boys’ lives. In 1996, Dr. Per Roth was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem for saving their lives.

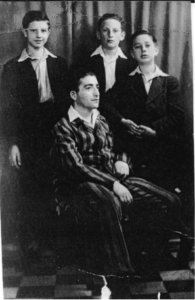

Only thirteen years old, Hirsz and the other boys walked for ten days before being liberated in Lubeck by British soldiers. Hirsz, Saul, Shmulik (Shmuel), and Leon stayed together and eventually ended up in an orphanage in the south of France. After many years of searching, Hirsz was able to reunite with his aunt Sarah Gonjuch in Peru in February 1952. In 1956, Hirsz married Norma Joels, whose family had escaped Lithuania before the war. They had four children: Jeannine Rivka, Golda, Salomon, and Masha.

Hirsz experiences in the Holocaust were deeply traumatic. His daughter Golda recalls:

“It was for him extremely hard to tell us his story; the first time that I heard most of the stories was when he gave testimony to the [USC SHOAH Foundation]. This interview took place in my home in Israel in 1998. It was in French, and I remember myself sitting on the stairs of my house listening and crying silently while trying to understand just a bit of what he lived through during those terrible times. For me, this was the beginning of a journey: to search, read, visit, and collect information, and also to share a little bit of his life story.”