Resistance against Nazism, including Jewish resistance, was far more widespread in occupied territories than commonly perceived.

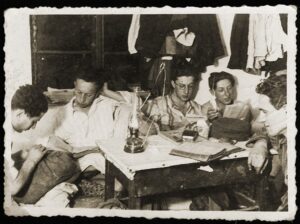

Jews living in ghettos and concentration camps engaged in a variety of nonviolent, silent protests. Many established underground groups to run illegal schools, printing presses, and social or political gatherings. One of their most significant forms of resistance was the unwavering commitment to their Jewish faith. Many continued to practice their religion in secret to maintain dignity and thus to defy their cruel and inhumane treatment. Resistance did not necessarily mean violent action. Rather, many Jews chose to resist in subtle and clandestine ways against the Nazi oppression.

Some Jews were able to acquire weapons and respond with armed resistance against the Nazis, with some violent uprisings in ghettos and concentration camps. The Warsaw ghetto uprising of April-May 1943 is a particularly notable example of resistance, as Nazis required over a month to defeat the combatants and retake the ghetto.

Especially young people tried to organize resistance. In Będzin’s ghetto Kamionka, they met in the “farma,” a small plot of land given to young people by the Jewish Council. Chajka Klinger and Miriam ‘Kasia’ Szancer were two young women in the underground resistance. Chajka, who grew up in a Hasidic family in Będzin, became a leader in the Zionist youth movement and in 1942 joined the resistance. Caught and tortured by the Nazis, she eventually escaped to Slovakia and settled in Israel. Miriam ‘Kasia’ Szancer was also caught by the Germans and rescued by Hirsch Barenblat, the head of Będzin’s Jewish ghetto police (whom she later married). Because of the active youth movement in the region, the resistance leader of the Warsaw Ghetto, Mordechai Anielewicz, came to Będzin in 1942 to help them get organized. Others, like Jane Lipski, escaped the ghetto. From their hiding places in the forests of Eastern Europe, they attacked Nazis who were roaming the countryside in their hunt for Jews. Some of these Jewish partisan units were able to enlist Allied support, especially by Soviet forces, in their fight against Germans.

On October 7, 1944, two young women from Będzin joined an armed uprising in Auschwitz-Birkenau. They assisted in a successful plot to destroy one of the gas chambers and crematoria. One of the women was Rose Rechnic‘s aunt Regina Safirsztain. For their participation in the resistance, the women were tortured and eventually hanged. Ella Liebermann-Shiber preserved the hanging of the women in one of her drawings.

For more information on Jewish resistance:

USHMM: Jewish Resistance

Yad Vasheen: Jewish Resistance

On Jewish partisans:

Nechama Tec, Defiance: The Bielski Partisans (Oxford University Press, 1993)